Have you ever had a hard time learning about some subject? Perhaps it’s a course you’re studying, perhaps it’s someone at work trying to teach you something.

And they’re talking and talking, and you’re hearing mountains of words and language, and you feel like you’re “drinking from a hosepipe” – i.e. receiving lots of information, but not understanding it, or forgetting it, or getting confused about what it means.

The funny thing is, there are so many things in life that we don’t seem to have any difficulty remembering. Think about the route you take to work or school. You probably don’t have too much difficulty remembering that. You can call to mind the way to the front-door of the house where you live, perhaps the street it’s on, the bus stop you go to and the bus that you take. Or take your circle of friends. You probably recall their names, facts about them, even how you met them (if you weren’t too young to remember).

We are able to remember some kinds of knowledge, and yet we seem to struggle immensely with others.

I would like to share one technique I’ve found useful, when a subject seems difficult to learn. I refer to it as “integration”, but there are probably other names for it already.

When I’m hearing some new piece of information and I really want to understand it, I try to connect it to something that I already know. And, especially (if possible) I try to connect it directly to myself, in a way that means something to me.

So, say I’m learning a new fact about how climate works in one particular part of the world, I’ll try to connect that fact to something I already know about climate, or about the world. And I try to discern how that fact is relevant to me, personally.

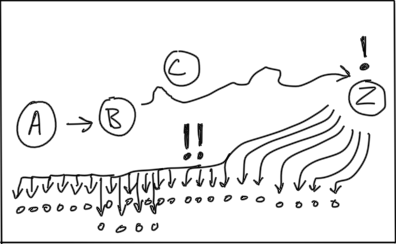

Often, (at least, initially), I don’t see a connection. It feel like a piece of floating, arbitrary data. And this is where, if possible, I ask questions to try and find that connection. So, if someone’s telling me about a climate phenomenon, I might ask them a question such as: well I thought climate was about ‘X’ or ‘Y’. But this fact you’re telling me about, how does it relate to that? How does the temperature in this place relate to the fact that it’s more humid in the tropics, near the middle of the equator? (A “fact”, or at least, an item of information, that I already grasp.)

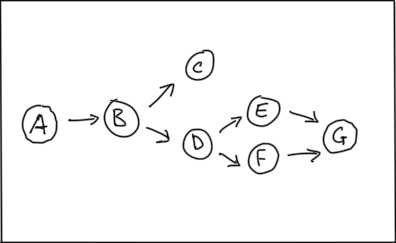

By asking such questions, I’m testing the things I’m hearing and discovering connections between the new information and the information I already recall. And if something I already knew turns out to have been a flawed understanding (at least from one perspective) then I’ll correct that, and, in doing so, build a nice “bridge” or “transition” between the old knowledge and the new knowledge.

Another kind of question I’ll ask is why this thing is being taught to me, or why it exists. So, say someone is informing me about a particular design technique. I’ll ask the question: why does this technique exist in the first place? Why not just do something simpler like ‘X’ or ‘Y’? By asking that question, the other person is called upon to explain to me further why that technique exists, what problem it solves, and in the process of doing so, I get a much stronger link between my previous understanding, and the new understanding. Rather than taking it as a given that this new technique happens to exist, I can form an understanding of why it exists and where it fits in to the “network” of other techniques.

One benefit to this “integration” technique is that it become easier to remember things. Just as when you go out your front door, you transition onto the street, and then to the bus stop, then onto the bus, etc., in a sequence or chain of knowledge, I find that I can remember things I’ve learned by following the connections I’ve made. Say I’ve learned a new design technique. If I find myself in a situation, which calls to mind some piece of knowledge I already have about design, and I connected that knowledge to a new technique, then I’ll recall that new technique at the right time, and perhaps apply it to the situation. I’ve got that information encoded mentally in such a way that it comes to me at the right time.

And that leads me to another benefit: recalling material at the right time. When you learn something new, which you worry about storing in your memory, you might also feel concerned about retrieving it at the right time and right context. I find that I’m much more likely to remember something, say a solution to a problem, at the right time, if I’ve integrated or connected it to the knowledge I currently draw upon, to solve that problem.

This technique isn’t guaranteed to work in every situation. I have found that there are times when the information is flowing much too fast. In those cases I’ll often try to quickly write down words and phrases for use later, perhaps to research later. Or I’ll try to get the information in a written format, which I can read at leisure.

I’m also sure that there are kinds of knowledge that can’t be connected to what one already knows. In areas like that, there are probably other techniques to look at using, for learning. Or perhaps there are some things that cannot be learned, at least, not in a conceptual manner.

But, for what it’s worth, I’ve found integrating to be highly useful in a wide range of learning scenarios.

Credits

The ideas presented in this article draw some inspiration from the learning theories and tools (such as concept mapping) of Joseph D. Novak, expressed in books such as Learning How to Learn (1984).